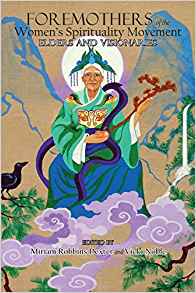

Foremothers of the Women’s Spirituality Movement: Elders and Visionaries

Edited by Miriam Robbins Dexter and Vickie Noble

Teneo Press, 2015

Review by Barbara Ardinger.

Foremothers of the Women’s Spirituality Movement: Elders and Visionaries is a valuable historical document on whose cover is a beautiful painting of Xiwangmu (a Queen Mother and one of the eldest Chinese deities) by artist and historian Max Dashú. The book opens with a list of fifteen of our foremothers who are no longer with us. Next come introductory essays by the book’s editors, Vicki Noble (co-creator of the Motherpeace Tarot) and Miriam Robbins Dexter (a protégée of Marija Gimbutas). The body of the book presents thirty-one personal essays by women of significance today in the community of the Goddess. Part 1, “Scholars,” gives us ten essays, including chapters by Carol P. Christ (I remember swapping horror stories with her about being young and female in academia in the 1970s), Elinor W. Gadon, and Riane Eisler. Part 2, “Indigenous Mind and Mother Earth,” presents seven essays by women like Luisah Teish (her chapter will break your heart), Starhawk, and Glenys Livingstone, who lives in Australia. In Part 3, “Ritual and Ceremony,” ritualists like Z. Budapest (her story is especially germane today), Mama Donna Henes (whose website is inspiring), and Ruth Barrett (the best ritualist I’ve ever worked with) write about their work. In Part IV, “Artists and Activists,” Judy Grahn, Cristina Biaggi (another fascinating artist), Donna Read (her films are, alas, available on Amazon only on VHS), and Lydia Ruyle (have you seen her Goddess Banners?) write about their work. Part 5, “Philosopher and Humanitarian,” is Genevieve Vaughan’s essay about her work, which includes building the Sekhmet Temple in Cactus Springs, Nevada, and establishing the International Feminists for a Gift Economy network. There is also an appendix with thirty-eight illustrations.

The women’s spirituality movement (also called feminist spirituality or spiritual feminism) began in tandem with the second wave of feminism in the late 1960s, when women finally noticed how patriarchal and filled with war most of the world is and nearly always has been since the peaceful Neolithic civilization of Old Europe was wiped out. First we took political action. We founded the women’s liberation movement, consciousness raising groups, and the National Organization for Women (NOW). In 1966 Barbara Jordan became the first black woman to win a seat in the Texas Senate; in 1968 Shirley Chisholm became the first black woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives—and then in 1972 she ran for president; and Bella Abzug won her seat in Congress in 1970 when she said a woman’s place is in the home and in the House. Gloria Steinem founded Ms. Magazine, and we read and reread the works of Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan, Audre Lorde, Kate Millett, and Marge Piercy, among others. (If you haven’t read the ovular books by these women, the time to do so is now.) The women who looked more closely at religion and spirituality in the 60s and 70s were our foremothers. Many of them worked and taught us about the Goddess and goddesses in every culture right up until their deaths.

A paragraph in Miranda Shaw’s essay, “Dakinis Dancing,” captures the essence and rationale of women’s spirituality:

[It] gained momentum from the discovery of traditions in which deity is honored and envisioned as female, the earth is sacred, and women channel the holy elixir of life and spiritual blessings. When the maleness of God was no longer absolute, the foundation of patriarchal privilege crumbled, exposing gender roles as cultural constructs. We were freed to explore and esteem women’s qualities. We claimed the authority of our experience and wisdom. We rejected the dualism that values the life and creations of the mind over the life and creations of the body. … We glory in capacities once stigmatized, cherishing our capacity for bonding and empathy as an alternative and antidote for the greed, hatred, and violence that threaten our well-being and very survival (p. 79).

How to explain why women’s spirituality took root and bloomed? Kathy Jones, founder of the beautiful Glastonbury Goddess Temple, believes that “a large number of mostly women have incarnated at this time to bring awareness of Goddess back into the world again” and that we are “the same souls who were alive at the ending of the Goddess cultures in ancient times. We have returned to bring Her back to human awareness. … We have to build everything again from the group up… (p. 211).

But, she continues, “we also bring back with us buried memories of the painful and shocking experiences we suffered when the Goddess Temples and cultures were attacked and destroyed by patriarchal forces.” She goes on with an observation that is highly germane today. “We were not always the completely innocent victims of oppression,” she explains. “Sometimes we betrayed each other to save our own skins. … We had to hide who we were…. (p. 212).

Ancient wounds still hidden in our unconsciousness “can undermine” the work we do to try to change the world. “Unexpressed hurts are often projected unconsciously onto our Goddess sisters” (Jones, p. 212) and can lead to divisiveness and what some of us call “witch wars.” Ruth Barrett discusses the current debates about who can be a Dianic Witch. Barrett has always created and led rituals dedicated to the Women’s Mysteries,” which include the blood events in our lives. Now some transgender people want to join rituals created for “women-born women.” Here is a bit of Barrett’s comment on this extremely divisive issue:

Recent debates over sex and gender, who is a woman and who is not (and who gets to decide), feels [sic.] sadly, to me, like another version of woman-hating that our Dianic tradition has always had to deal with… (p. 220).

As you read her chapter, consider the implications of this issue. Read every chapter carefully and consider all the issues and the long history that women still have to deal with in a world that is becoming hyper-violent as, several chapters say, patriarchy has figured out that its time is about done and the boys are fighting as hard as they can to resist the return of the Goddess and Her strong, determined women. As Charlene Spretnak writes early in the book:

What did our movement accomplish? … We grasped that patriarchal religion—with its hierarchical institutions ruled over by a male god as Commander-in-Chief—was not simply “religion” but … a type [her emphasis] of religion that had evolved as a comfortable fit for the male psyche. This decentering of male-oriented religion freed women to evolve our own modes of deep communion with the sacred whole (p. 22).

Our work obviously has further to go. Just ask every one of our sisters who contributed a chapter to this book. Although some of the essays seem over-long and some are “I did this and then I did that and then I did something else,” every contribution to the book is well worth reading, especially by younger women who may not know about our history (which some spiritual feminists call our herstory). This book should be on the shelf of every woman in the world. (Well, at least shelves belonging to women who can read English.)

The only significant problem in this amazing book is that the illustrations are all in the appendix instead of where they are first mentioned, so we have to page through the book (or dog-ear the first page of the appendix) if we want to see what Max Dashú, Cristina Biaggi, and Lydia Ruyle, for example, are talking about. But except for this inconvenience, it’s a perfectly splendid book.